The Theatricality of Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonatas and the Theater of History: Preliminary Considerations for Harpists / LA TEATRALITA’ DELLE SONATE DI DOMENICO SCARLATTI E IL TEATRO DELLA STORIA: ALCUNE PREMESSE PER ARPISTI

by Lorenzo Montenz

(Englis and Italian test)

Premise

This study day will address the transcription of Domenico Scarlatti’s keyboard sonatas for the harp. While originally conceived for keyboard instruments, these sonatas appear to possess a singular affinity with the harp, an association evidenced as early as Félicité de Genlis’s historical accounts.

Our inquiry will delve into the historical corroboration of this affinity, examining the various historical manifestations it has assumed. Furthermore, we will critically analyze the challenges inherent in adapting Scarlatti’s musical text to the harp’s unique string configuration. Finally, we will explore the technical solutions proposed within historical transcriptions and those suggested by harp treatises contemporary to Scarlatti’s oeuvre.

First, however, allow me to briefly delineate the historical and aesthetic context in which these works were conceived.

You might be thinking that these few minutes would be better spent discussing fingerings, irregular accentuation, or the ornamentation of the sonata currently on your music stand. You might believe that your audience hears these technical details, while stories of kings, princes, and wars remain unheard. We will, indeed, have ample time to address technical matters. However, I genuinely believe that for an artist, for a professional in culture—which is what you are—venturing into the universe of history encapsulated within those two sheets of paper on your music stand is as essential as possessing the technical tools to satisfy your audience. This is because the pleasure an artist derives from exploring the world and history reflected in those notes is no less important, nor less necessary, than the pleasure the audience experiences when hearing it recounted in your concerts.

This, in my opinion, isn’t a secondary or even an accessory reflection, even if the discussion doesn’t have an immediate impact on instrumental technique or the specific technical solutions to adopt. Yet, it sometimes strikes me that in musical education, the question “How do I play it?” has gained the upper hand, if not entirely eclipsed, the question “What should I play?”

If, instead of being in a conservatory, we were in an academy of fine arts, before asking whether to paint on canvas, wood, or paper, with oils, watercolors, or pastels, wouldn’t we first ask: “What is the subject?” One might think the subject is right there on our music stand. But does the subject of our musical narrative truly exhaust itself in sounds, note values, and harmonies to be deciphered?

Naturally, the practice of musical performance is characterized by a very different path from that of producing a visual artwork. And certainly, many of us have heard extraordinary concerts by soloists who knew little or very little about the historical and cultural context of the music on their stands. The point, in my opinion, isn’t what the audience missed, but rather what the artist missed.

LA TEATRALITA’ DELLE SONATE DI DOMENICO SCARLATTI E IL TEATRO DELLA STORIA: ALCUNE PREMESSE PER ARPISTI

PREMESSA

Materia di questa nostra giornata di studi è la trasposizione delle sonate di Scarlatti dagli strumenti a tastiera, per cui sono state concepite, alla cordiera dell’arpa, per la quale, fin dalla testimonianza di Félicité de Genlis, paiono aver avuto una singolare affinità. Ci occuperemo della sostenibilità storica di questa affinità, delle vesti storiche che ha assunto, delle problematiche di adattamento del testo musicale delle sonate alla cordiera dell’arpa e delle soluzioni tecniche proposte nelle trascrizioni storiche o suggerite dai trattati d’arpa più prossimi all’opera di Scarlatti.

Prima però, per pochi minuti, lasciatemi delineare il contesto storico ed estetico in cui queste opere hanno conosciuto la loro gestazione.

Magari state pensando che questi dieci minuti sarebbero meglio spesi ragionando delle diteggiature, dell’accentazione irregolare, dell’ornamentazione della sonata che avete sul leggio. Che queste cose il pubblico le sente, le storie dei re, dei principi, delle guerre invece non si sentono. Avremo tutto il tempo per parlare di questioni tecniche. Ma io credo veramente che per un artista, per un professionista della cultura –ché questo siete voi- avventurarsi nell’universo della storia racchiusa in quei due fogli di carta che avete sul leggio, sia necessario quanto possedere gli strumenti tecnici per soddisfare il vostro pubblico. Perché il piacere che prova un artista esplorando il mondo e la storia che si riflettono in quelle note è né meno importante, né meno necessario del piacere che prova il pubblico a sentirselo raccontare nei vostri concerti.

Questa, a mio parere, non è una riflessione secondaria e neppure accessoria, anche se il discorso non ha una ricaduta immediata sulla tecnica strumentale o sulle soluzioni tecniche da adottare. Ma a volte a me pare che nel percorso formativo musicale la domanda “come lo suono?” abbia preso il sopravvento, se non addirittura eclissato la domanda “cosa debbo suonare?”.

Se invece che in un conservatorio fossimo all’accademia di belle arti, prima di domandarci se dipingere su tela, su tavola o su carta, ad olio, acquerello o pastello, non ci chiederemmo: ”qual è il soggetto?”. Si potrebbe pensare che il soggetto noi ce l’abbiamo lì sul leggio. Ma veramente il soggetto della nostra narrazione musicale si esaurisce in suoni, valori, armonie da decriptare?

Naturalmente la prassi dell’esecuzione musicale è caratterizzata da un percorso molto diverso da quello della produzione di un’opera figurativa, e certo è capitato a tanti di noi di aver ascoltato concerti straordinari di solisti che poco o molto poco conoscevano del contesto storico e culturale della musica che avevano sul leggio. Il punto, a mio giudizio, non è quello che si è perso il pubblico, ma quello che si è perso l’artista.

The Theatricality of Two Pages

As is well-known, the majority of Scarlatti’s sonata corpus reached us in two series of manuscripts copied between 1742 and 1759. The publication of the Essercizi dates back to 1738.

It’s by no means certain that all these keyboard works originated during the composer’s long Iberian period (which spans from 1720 to his death in 1757). Nevertheless, many of them bear the imprint of Iberian musical folklore in general, and Andalusian in particular. Analytical research has very appropriately dedicated itself to exploring and highlighting these influences. Dance rhythms, harmonic structures, gestures, and theatricality attributable to that cultural context are essential for understanding the musical text and for a mature performance.

In my view, this perspective still has something to tell us if, while keeping our focus firmly on Iberian-Andalusian aesthetics, we make the effort to broaden our scope from the realm of mere musical aesthetics to that of the corresponding aesthetic culture. This requires us to truly strive to understand what the term “theatricality” signifies in reference to the Sonatas.

Enrico Baiano, an exceptionally profound scholar of Scarlatti’s work and aesthetics, articulates with remarkable clarity the inherent theatrical nature embodied in these brief compositions: “In Scarlatti’s sonatas, almost everything is theatrical: the introduction is equivalent to the raising of the curtain; the themes are characters, each with its own personality; the various sections of the piece are scenes, while developments and modulations are plot points. The blatant, sometimes eccentric, musical gestures, sudden pauses, unexpected modulations, and abrupt, disconcerting shifts in mood are the infallible tricks of a seasoned theater professional who knows how to command the stage.”

Keep these words in mind, because it’s difficult to find a more functional interpretive lens for the Sonatas than this. To grasp its full significance, I’d now like you to join me in exploring an even broader scene than that of a theater stage.

LA TEATRALITA’ DI DUE PAGINETTE

La porzione maggiore del corpus sonatistico scarlattiano, come è noto, ci è giunta in due serie di manoscritti copiati tra il 1742 e il 1759. Al 1738 risale invece la pubblicazione di Essercizi. Non è affatto scontato che tutte queste opere per tastiera abbiano visto la luce nel lungo periodo iberico del compositore (che va dal 1720 alla morte nel 1757) eppure molte di esse recano la traccia del folclore musicale iberico in generale e andaluso in particolare. Molto opportunamente la ricerca analitica si è largamente dedicata ad esplorarne e metterne in luce gli influssi. Ritmi di danza, strutture armoniche, gestualità e teatralità riconducibili a quel contesto culturale sono un dato imprescindibile per la comprensione del testo musicale e per una resa matura.

A mio avviso questa prospettiva ha ancora qualcosa da dirci se, tenendo fissa l’attenzione sull’estetica iberico-andalusa, compiamo lo sforzo di allargare il focus dal campo della mera estetica musicale a quello della corrispondente cultura estetica, e se ci sforziamo di capire veramente cosa significhi il termine “teatralità” in riferimento alle Sonate.

Enrico Baiano, profondissimo conoscitore dell’opera di Scarlatti e della sua estetica, esprime in modo chiarissimo la natura teatrale che si incarna in queste brevi composizioni: “Nelle sonate di Scarlatti quasi tutto è teatrale: l’introduzione equivale al levarsi del sipario: i temi sono personaggi, ognuno con la propria personalità: le varie sezioni del pezzo sono scene, mentre gli sviluppi e le modulazioni sono momenti dell’intreccio. I gesti musicali plateali, a volte strampalati, le pause improvvise, le modulazioni inaspettate, gli improvvisi e sconcertanti cambi d’umore sono trucchi infallibili di un teatrante esperto che sa come tenere la scena”.

Tenete a mente queste parole, perché è difficile trovare una traccia interpretativa delle Sonate più funzionale di questa. E per capirne la portata vorrei che mi seguiste ora ad esplorare una scena ancora più ampia di quella del palco di un teatro.

The Theater of Faith and Superstition

The Spanish musical soundscape possesses such distinctive idioms that no musician can claim immunity from their allure. As is well-known, the encounter with Spanish music profoundly impacted Domenico Scarlatti’s creative sensibility, prompting him to transcribe the impressions of this novel rhythmic and sonorous universe into his scores.

Yet, as attested by the memoirs of diplomats and travelers, much else captivated the sensibilities and imagination of those who crossed the borders of the Catholic Monarchs. The prevailing social, religious, and political climate, along with the historical coexistence of diverse faiths and ethnicities—at times tolerated, at times fiercely persecuted—had, over centuries, forged a truly singular cultural atmosphere marked by its strident contradictions.

For over a century, the entirety of Catholicism was profoundly shaped by Spanish spirituality, which revitalized the modes of belief and prayer throughout the West. The sensual abandonment articulated in Teresa of Avila’s The Way of Perfection and the intimate mystery evinced in John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul represent a point of no return for the spiritual experience of the entire Western world. However, in the very year Teresa penned The Interior Castle, her compatriots were simultaneously spilling torrents of blood in the Sack of Antwerp, the most infamous of the “Spanish Furies” that ravaged Flanders, sending shivers of horror through both Catholic and Protestant Europe. This was a nation perpetually in prayer, yet perpetually at war—devout and sanguinary, even when religious conflicts eventually yielded to wars of succession.

In Sonata K. 224, the initial light and carefree gaiety transitions into the solemnity of an ascending fifths progression. The textures of these two episodes represent contrasting worlds in terms of technique, structure, and emotional affect. The playful, agile ‘finger-work’ seems to rush headlong without pause, suddenly culminating in an entirely contemplative progression. The partimento literature, from which Scarlatti largely received his training, frequently proposes this sequence as suitable for polyphonic harmonization. Scarlatti seizes upon its intrinsic character to construct a four-voice architecture that immediately evokes the solemnity of a liturgy. Indeed, the identical sequence is found in the organ Sonata K. 287, exhibiting a superimposable polyphonic rendition, albeit realized without diminutions.

IL TEATRO DELLA FEDE E DELLA SUPERSTIZIONE

L’universo musicale spagnolo conserva idiomi così caratteristici che nessun musicista può dirsi indenne dal loro richiamo. L’impatto con la musica spagnola, come ben sapete, non lasciò affatto indifferente l’animo creativo di Domenico Scarlatti, che tradusse in partitura le impressioni di questo nuovo universo ritmico e sonoro.

Eppure, ci dicono le memorie di diplomatici e viaggiatori, molto altro colpiva la sensibilità e la fantasia di chi varcava i confini dei Re cattolici. Il clima sociale, religioso, politico, la storica coesistenza di fedi ed etnie diverse ora tollerate, ora perseguitate duramente, aveva generato nel corso dei secoli un’atmosfera culturale assolutamente singolare nelle proprie stridenti contraddizioni.

Per oltre un secolo la cattolicità intera fu segnata dalla spiritualità spagnola che rinnovò il modo di credere e di pregare dell’occidente. L’abbandono sensuale del Cammino di perfezione di Teresa d’Avila, il mistero che che si fa prossimo nella Notte oscura di Giovanni della croce sono un punto di non ritorno dell’esperienza spirituale dell’occidente intero. Ma nello stesso anno in cui Teresa scrive il Castello interiore i suoi connazionali versano a fiumi il sangue dell’eccidio di Anversa, la più celebre delle furie spagnole che insanguinarono le Fiandre facendo trasalire d’orrore l’Europa cattolica e protestante. Una nazione sempre in preghiera, una nazione sempre in guerra. Devota e sanguinaria, anche quando le guerre di religione cederanno il passo a quelle di successione.

Nella Sonata K224 la leggera e spensierata allegria dell’esordio trapassa nella solennità di una progressione per quinte ascendenti. Le tessiture dei due episodi sono due mondi che si scontrano nella tecnica, nella struttura, nelle emozioni. La corsa giocosa, tutta in punta di dito, sembra lanciata a perdifiato senza potersi fermare, e improvvisamente sfocia in una progressione tutta contemplativa. La letteratura dei partimenti a cui Scarlatti si è largamente formato, propone sovente questa sequenza come adatta all’armonizzazione polifonica. Scarlatti ne coglie l’indole per costruirvi un’architettura a quattro voci che richiama subito la solennità di una liturgia. La stessa identica sequenza si ritrova infatti nella sonata per organo K 287 con una resa polifonica sovrapponibile a questa, ma realizzata senza diminuzioni.

The devotion of the Spanish populace, and the solemnity and folklore of its religious festivals, were unparalleled within the complex panorama of Europe’s national churches. Alongside the rigor of post-Teresian spirituality, a profound sense of devotion, one that extensively transcended the boundaries of superstition, permeated every social stratum. The renowned Spanish Inquisition was still actively at work, yet contrary to common perception, it was no longer burning witches. Trials were still conducted; precisely during Scarlatti’s period, the Logroño Inquisition recorded nearly fifty witchcraft trials, all of which concluded with the acquittal of the accused. Witchcraft no longer interested the theological judges, but it still obsessed the populace, who widely denounced witches and sorcerers. This obsession with witchcraft in Spain considerably surpassed the chronological limits of the 18th century, continuing to infest the pictorial nightmares of Francisco Goya.

Some of the sonatas you perform feature the characteristic effect of a rhythmic-melodic figure repeated numerous times. In my day, we were taught to play one time forte, then piano, and so on—this was the pinnacle of ancient aesthetics found in harp schools at that time. But here, it simply doesn’t work. The relentless, unchanging repetition generates a singular effect of suspended temporal perception: a kind of musical hypnosis. Several scholars of the Sonatas connect this compositional device to the flamenco tradition. However, the suspension of temporal perception is also one of the recurring and defining experiences of the sabbat, as reported in inquisitors’ manuals and witchcraft trials. Clearly, the common ancestor of both popular and sabbatic dance lies in Bacchic rites, but that is not a topic of interest here. What I find stimulating and engaging, however, is to attempt to perceive within that series of repeated figures on the page the trace of an ancient, visceral, enchanting dance, and to try to convey this to your listeners.

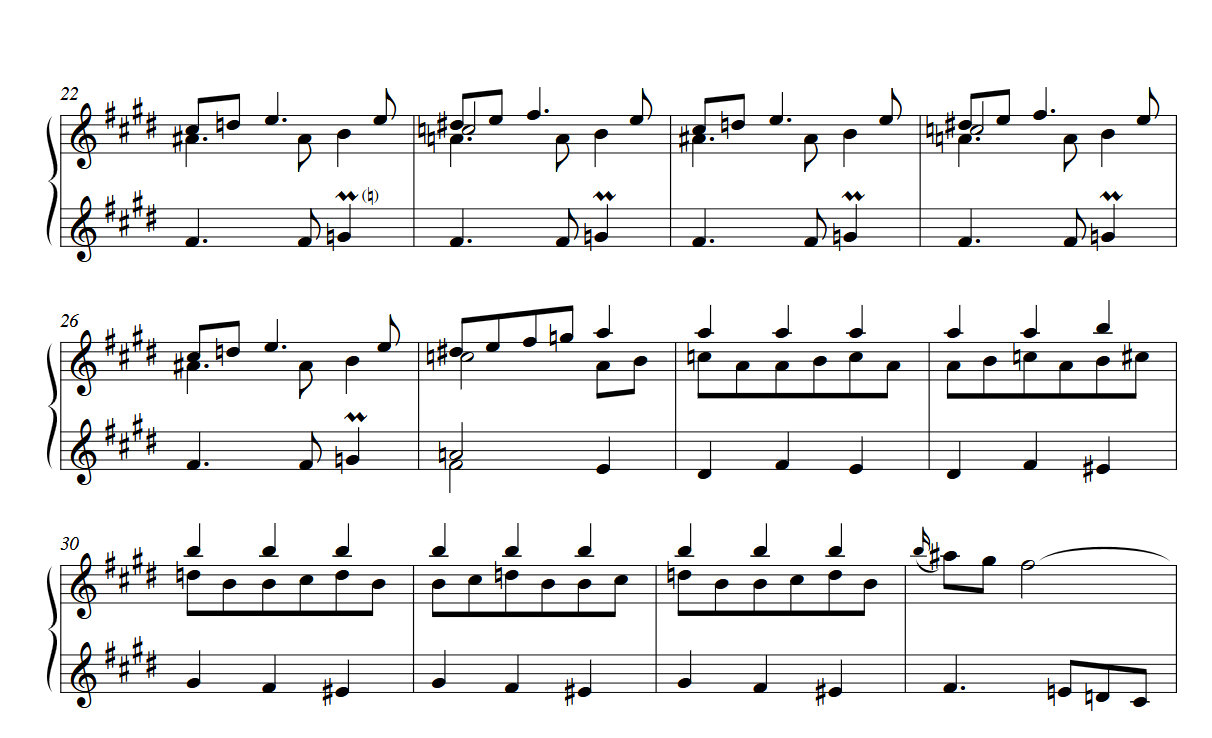

I invite you to listen, for instance, to Sonata K. 216, where the effect of repetitions, the flowing from one module to another without a recognizable scheme, and the difficulty in identifying a principle of symmetry engender a veritable sense of vertigo in the listener. I will now present some passages from the sonata.

La devozione del popolo spagnolo, la solennità e il folclore delle sue feste religiose non avevano pari nel complesso panorama delle chiese nazionali europee. Accanto al rigore della spiritualità post teresiana convive in ogni ceto sociale un senso della devozione che scavalca a grandi falcate il limite della superstizione. La celebre Inquisizione spagnola è ancora alacremente al lavoro, ma contrariamente a quanto si può pensare non brucia più le streghe. Processi se ne celebrano ancora: proprio nel periodo scarlattiano l’Inquisizione di Logroño registrò quasi cinquanta processi di stregoneria, tutti conclusi con l’assoluzione degli imputati. La stregoneria non interessava più ai giudici teologi, ma ossessionava ancora la gente che denunciava largamente streghe e stregoni. Un’ossessione, questa della stregoneria, che in spagna superò abbondantemente i limiti cronologici del secolo XVIII infestando ancora gli incubi pittorici di Francisco Goya.

Alcune delle sonate che voi eseguite presentano l’effetto caratteristico di una figura ritmico-melodica ripetuta numerose volte. Ai miei tempi ci insegnavano a suonare una volta forte, una piano, e così via…era il massimo dell’estetica antica che si trovava nelle scuole d’arpa a quei tempi. Ma qui non funziona proprio. La ripetizione sempre uguale genera un singolare effetto di sospensione della percezione del tempo: una sorta di ipnosi musicale. Diversi studiosi delle Sonate mettono in relazione l’espediente compositivo con la tradizione del flamenco. La sospensione della percezione del tempo è però anche una delle esperienze ricorrenti e caratterizzanti del sabba riportate nei manuali degli inquisitori e nei processi di stregoneria. Chiaramente l’antenato comune di danza popolare e danza sabbatica sono i riti bacchici, ma non è argomento di alcun interesse in questa sede. Quello che invece trovo stimolante e interessante è provare a vedere in quella serie di figure ripetute che avete sulla carta, la traccia di una danza antica, viscerale, incantatrice e provare a farla sentire ai vostri ascoltatori.

Vi invito ad ascoltare, ad esempio, la sonata k 216 in cui l’effetto delle ripetizioni, il fluire di un modulo in un altro senza uno schema riconoscibile, e la difficoltà di individuare un principio di simmetria ingenerano nell’ascoltatore una vera e propria vertigine. Riporto di seguito alcuni passaggi della sonata:

Sonata K 216. b. 22-32

Sonata k 216. b. 68 e seguenti.

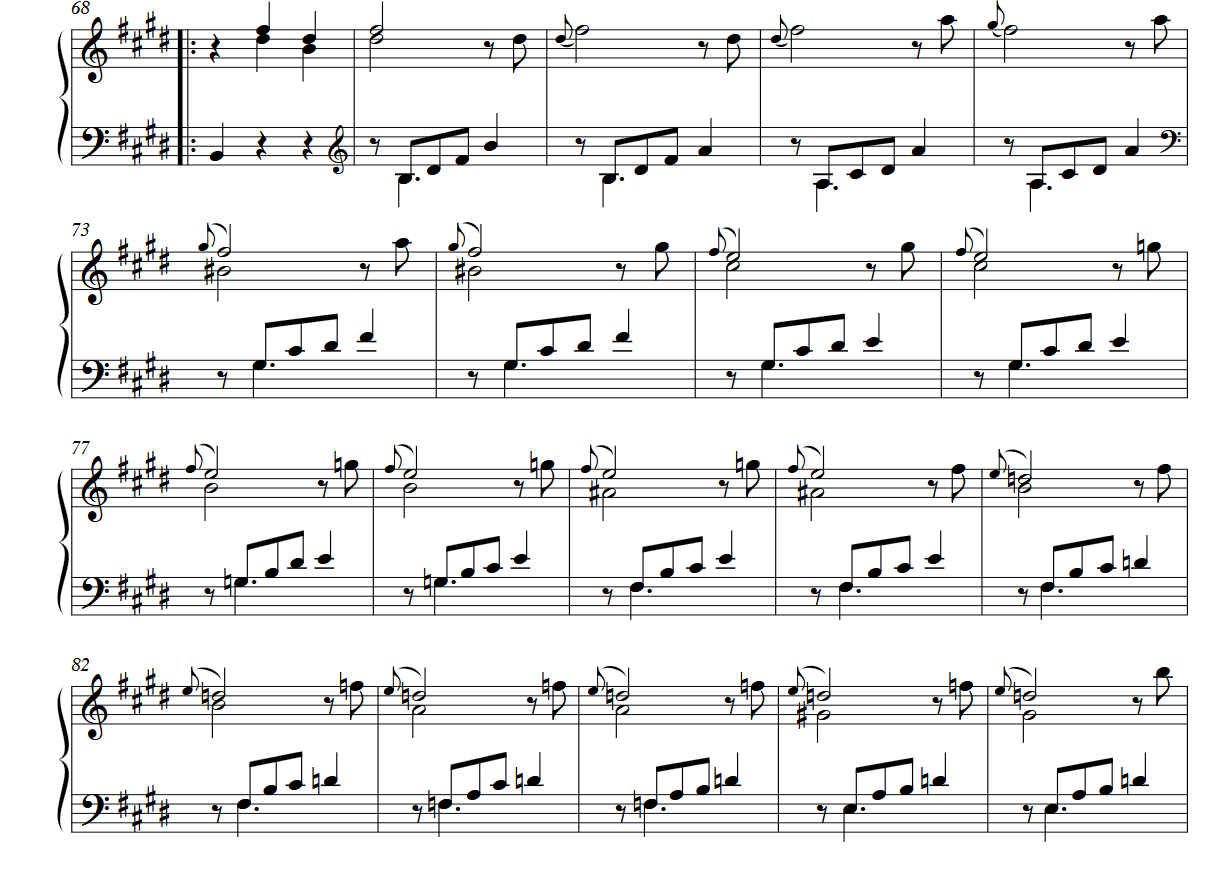

To cite another example, consider measures 84-99 of K. 193, where the graceful fluidity of the musical text is interrupted by a perturbing, obstinate, yet harmonically fluid and unstable element.

Cito ancora, a titolo di esempio, le misure 84-99 di K 193, dove la graziosa scorrevolezza del testo è interrotta da un elemento perturbante

Sonata K 193

The Theater of History

When Domenico Scarlatti arrived in Spain, history was ironically penning a new chapter. Philip V, grandson of the Sun King, raised and educated at Versailles, now moved through the Escorial amidst the shadows of the extinct Spanish Habsburgs. The mad Bourbon king settled onto the throne vacated by the last mad Habsburg king. The Peace of Utrecht had solidified this throne, but it also marked the decline of Hispanic hegemony in European politics. The tragedy of the Habsburgs was transforming into the comedy of the Bourbons, as depicted by Louis Michel van Loo in 1743.

IL TEATRO DELLA STORIA

Quando Domenico Scarlatti giunge in Spagna la storia sta scrivendo con ironia una nuova pagina. Filippo V, il nipote del Re sole, cresciuto ed educato a Versailles, si muove ormai all’Escorial tra le ombre degli estinti Asburgo di Spagna. Il re folle dei Borbone si accomoda sul trono lasciato libero dall’ultimo re folle degli Asburgo. La pace di Utrecht ha reso saldo questo trono, ma ha anche segnato il tramonto dell’egemonia ispanica sulla politica Europea. La tragedia degli Asburgo si va trasformando nella commedia dei Borbone che Louis Michel van Loo ritrasse nel 1743.

To the spectator’s left are Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias and heir to the Spanish throne, and Maria Barbara of Braganza, in whose service Domenico Scarlatti was employed. Along with Infanta Maria Victoria, future Queen of Portugal, they form a distinct group, being the children of the king’s first marriage. Philip V, semi-demented, does not occupy the center of the composition, but sits slightly off-center to the right of his wife, Elisabetta Farnese, whom he regards with a stolid expression. It was for him that, according to C. Burney’s account, Farinelli sang “Pallido il sole” and “Per questo dolce amplesso” from J. A. Hasse’s Artaserse every evening from 1737 until the monarch’s death. And it was precisely to prevent the king from abdicating in favor of his son from his first marriage that Elisabetta Farnese clung to the spell Farinelli exercised over the sovereign.

Indeed, the Queen is the true heart of the Hispanic monarchy. She rests her arm on the crown cushion; she is enveloped in the regal mantle, which barely conceals the hereditary corpulence of the Farnese family. Positioned between the king and queen is their son, Luigi Antonio, Archbishop of Toledo at seven and cardinal at eight. He would later relinquish the purple to marry. Then come Philip, also a son of Elisabetta, who would become Duke of Parma after his brother Charles, and Louise Élisabeth of France, one of “mes dames,” the daughters of Louis XV whose teachers included J. B. Forqueray, P. Beaumarchais, J. Duphly, and A. L. Couperin. It was she who brought to Parma the first core collection of musical instruments and scores (including some works for harp) that now comprise the Bourbon collection of the Palatine Musical Fund.

After Louise Élisabeth, depicted standing in the background, is Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela, who would marry the Dauphin of France. Her austere and reserved character ill-suited her to life at the French court, whose frivolity she detested and whose hostility she endured. She unreservedly condemned the presence of Madame de Pompadour at court, whom she habitually referred to as “maman putain.” She found a faithful and harmonious companion in her husband, Dauphin Louis, but would die in childbirth little more than a year after her marriage. Next to her, we see Infanta Maria Antonia, who would become Queen of Sardinia after Louis XV rejected the Spanish proposal to make her the new Dauphine upon her sister Maria Teresa Rafaela’s death. For her, Benedetto Alfieri reorganized the apartments of the Duchess of Aosta in the Royal Palace of Turin. To the spectator’s far right stands Maria Amalia of Saxony with her consort, Infante Charles. They would be Dukes of Parma, then sovereigns of Naples and Sicily, and finally sovereigns of Spain.

This portrait encapsulates the political scene of those times: the concluded wars of succession and the peace sanctioned by various dynastic marriages; the declining Spain and the contending France and Austria vying for hegemony in the West; Flanders and Portugal, the Two Sicilies and Parma. And the history of nations and their upheavals is reflected in the stories of the characters who inhabit this grand painting: sympathies, antipathies, happy and unhappy marriages, great hopes and bitter disappointments, jealousies, hatreds, alliances, calculation, and madness. The theater of the world, the theater of the court, the theater of life.

So, what thread connects this rich tapestry of individual lives and grand history to the vibrant fabric of Scarlatti’s music? I want to avoid the pitfall of far-fetched interpretations, those that might try to neatly link a specific historical event to a particular Sonata. Yet, I believe the peculiar aesthetic of 18th-century courts, where the clang of swords was often replaced by the chime of wedding bells uniting royal lineages, finds an echo in the emotional landscape of certain Sonatas. Their marvelous arrangements of suspended cadences, their poignant silences, their subtle reticences, and their often-unexpected resolutions seem to capture something of that era’s unique spirit. Just to offer an illustration, consider Sonata K 497, which, incidentally, translates beautifully to the harp.

A sinistra dello spettatore sono Ferdinando, principe delle Asturie ed erede al trono di Spagna, e Maria Barbara di Braganza, al cui servizio si trova Domenico Scarlatti. Insieme all’infanta Maria Vittoria, futura regina di Portogallo, formano un gruppo a parte, in quanto figli del primo matrimonio del re. Filippo V, semidemente, non occupa il centro della composizione, ma siede leggermente decentrato alla destra della moglie Elisabetta Farnese, verso cui guarda con volto stolido. E’ per lui che, secondo la testimonianza di C. Burney, Farinelli, a partire dal 1737 e fino alla morte del sovrano cantò ogni sera Pallido il sole e Per questo dolce amplesso dall’Artaserse di J. A. Hasse. E fu proprio per evitare che il re abdicasse in favore del figlio di prime nozze che Elisabetta Farnese si aggrappò alla malia esercitata da Farinelli sul sovrano.

E’ infatti la regina il vero cuore della monarchia ispanica. Lei poggia il braccio sul cuscino della corona, lei è avvolta dal manto regale, che a malapena dissimula la pinguedine ereditaria dei Farnese. Tra il re e la regina è posizionato il figlio Luigi Antonio, Arcivescovo di Toledo a sette anni e cardinale a otto. Lascerà poi la porpora per sposarsi. Vengono Filippo, anch’egli figlio di Elisabetta, che diverrà duca di Parma dopo Carlo suo fratello, e Luisa Elisabetta di Francia, una delle mes dames, le figlie di Luigi XV che ebbero tra i loro maestri J. B. Forqueray, P. Beaumarchais, J. Duphly e A. L. Couperin. Fu proprio lei che portò a Parma il primo nucleo di strumenti musicali e di spartiti (tra cui alcune opere per arpa) che compongono oggi la collezione Borbone del Fondo musicale palatino.

Dopo Luisa Elisabetta troviamo ritratte, in piedi in secondo piano, l’infanta Maria Teresa Raffaella, che sposerà il delfino di Francia. Carattere austero e schivo mal si adattò alla vita della corte francese di cui detestava la frivolezza e di cui subì l’ostilità. Condannò senza riserve la presenza a corte di Madame de Pompadour, che si abituò a chiamare “maman putain”. Trovò nel marito, il delfino Luigi, un compagno fedele e affiatato, ma morirà di parto poco più di un anno dopo il matrimonio. Accanto a lei vediamo l’infanta Maria Antonia , che sarà regina di Sardegna, dopo che Luigi XV rifiutò la proposta spagnola di farne la nuova delfina alla morte della sorella Maria Teresa Raffaella. Per lei Benedetto Alfieri risistemò gli appartamenti della Duchessa d’Aosta di Palazzo Reale a Torino. All’estrema destra dello spettatore sta Maria Amalia di Sassonia con il consorte, l’infante Carlo. Saranno duchi di Parma, poi sovrani di Napoli e Sicilia, e infine sovrani di Spagna.

In questo ritratto c’è la scena politica di quei tempi: ci sono le guerre di successione concluse e la pace sancita dai vari matrimoni dinastici, ci sono la Spagna al tramonto e la Francia e e l’Austria che si contendono l’egemonia dell’occidente. CI sono le Fiandre e il Portogallo, le Due Sicilie e Parma.

E la storia delle nazioni e dei loro rivolgimenti si riflette sulle storie dei personaggi che abitano questo grande dipinto. Simpatie, antipatie, matrimoni felici ed infelici, grandi speranze e cocenti delusioni, gelosie. odi, alleanze, calcolo e follia. Il teatro del mondo, il teatro di corte, il teatro della vita.

Quale relazione tra questo grande intreccio di storie e di storia e il testo scarlattiano? Vorrei tenermi alla larga dal rischio di interpretazioni improbabili che mettano in relazione questo o quell’episodio con una data Sonata; ma al tempo stesso credo che il bizzarro estetismo delle corti settecentesche, che sostituiscono le guerre con i matrimoni tra rampolli delle case regnanti, trovi un riflesso emozionale nella meravigliosa composizione di cadenze sospese, silenzi, reticenze, esiti inattesi di alcune Sonate. Cito, giusto a titolo di esempio, una Sonata che all’arpa funziona piuttosto bene: la K 497

At bar 35, we encounter the first surprise: a deceptive cadence with a suspension, resolving to the VI degree. This VI degree then transforms into an auxiliary leading-tone 3/6 chord, leading to a cadence on the dominant of the dominant (the sonata is in D major). Then, silence. We are subsequently transported to another universe. C major. However, because it follows an E 3♯ chord, the ear tends to perceive the overtones of A minor alongside the C. Yet, C is not a mere disguise for A minor; it is a disguise for itself. However, the arpeggios, moving through a descending perfect fourth progression, truly lead us to perceive an A minor. Throughout this passage, both the harmonic progression and its realization through long arpeggios evoke a sense of fluidity in the listener, transporting them to a world parallel to the one heard before the grand pause. Much like in our portrait, the unexpected developments born from bizarre pairings write a history that, despite everything, never ceases to enchant.

If you observe the painting for another moment, you’ll notice a group of musicians looking out from the choir loft. This is certainly a fitting tribute to the role musicians held in the complex life of the Spanish court and in the interplay of its unstable balances. At the time this work was created, Domenico Scarlatti and Carlo Broschi (Farinelli) could very well have been looking out from that very choir loft.

Imagine the composer of your sonatas peering out: do you see a mere employee observing his employers, or rather a seasoned theatergoer observing the theater of history? I imagine Domenico Scarlatti a bit like that. Silent. Not because he was actually so, but because history, for one reason or another, has scattered the voice of his documents, his letters, most of his compositions. It has instead enclosed his worldview within the bottle of his Sonatas, entrusting it to the sea of history and art. Today, we listen to those synthetic and incisive words which, it seems to me, betray the witty, ironic, meditative, profound, and essential spirit with which the author contemplated his world and, I believe, judged it. Slightly twisting a beautiful expression by Augustine of Hippo, I think that world was a theater, and Domenico its spectator: Theatrum mundus, spectator Dominicus.

A b. 35 troviamo la prima sorpresa di una cadenza falsa, con ritardo, al VI grado; poi il VI grado diventa una 3/6 di sensibile accessoria per cadenza alla dominante della dominante (la sonata è in re maggiore). Poi silenzio. Poi ci troviamo in un altro universo. Do maggiore, Ma venendo da un accordo di Mi 3# l’orecchio tende a sentire insieme al Do gli armonici di La minore. E invece il Do non è la maschera di La minore, ma è la maschera di sé stesso; ma poi gli arpeggi su progressione per quarta discendente ci potano davvero a sentire un La minore, e in tutto questo tanto la progressione armonica che la realizzazione per arpeggi lunghi ingenera nell’ascoltatore un senso di fluidità in un mondo parallelo a quello ascoltato fino alla grande pausa. Come nel nostro ritratto gli sviluppi inattesi di abbinamenti bizzarri scrivono una storia che, nonostante tutto, non smette di incantare.

Se osservate ancora per un momento il dipinto noterete un gruppo di musicisti che si affacciano dalla cantoria. E’ certo un giusto tributo al ruolo che i musicisti ricoprivano nella complessa vita della corte spagnola e nel gioco dei suoi instabili equilibri. Al tempo in cui quest’opera fu realizzata dalla cantoria avrebbero benissimo potuto affacciarsi Domenico Scarlatti e Carlo Broschi. Immaginate l’autore delle vostre sonate che si affaccia: ci vedete un dipendente che osserva i suoi datori di lavoro, o piuttosto uno spettatore ben pratico di teatro, che osserva il teatro della storia? Ecco io Domenico Scarlatti me lo immagino un po’ così. Silenzioso. Non perché lo fosse realmente, ma perché la storia, per una ragione o per un’altra, ha disperso la voce dei suoi documenti, delle sue lettere, delle maggior parte delle sue composizioni, e ha racchiuso la sua visione del mondo nella bottiglia delle Sonate affidata al mare della storia e dell’arte. Oggi noi ascoltiamo quelle sintetiche e incisive parole che, mi pare, tradiscono lo spirito arguto, ironico, meditativo, profondo, essenziale con cui l’autore contemplava il suo mondo e, penso, lo giudicava. Storpiando un po’ una +bellissima espressione di Agostino d’Ippona penso che quel mondo fosse un teatro e Domenico il suo spettatore: Theatrum mundus, spectator Dominicus.

The Spanish Theater

Speaking of theatricality, we can now indeed imagine the impact of Spanish theater on the son of the most celebrated opera composer of his era. Eighteenth-century Spanish theater still embodied both the eclectic spontaneity of Lope de Vega and the dramatic intensity of Pedro Calderón de la Barca. The treatise writer Ignacio de Luzán, in his monumental Poética o reglas de la poesía, published in 1737, defined tragedy thus: “A dramatic representation of a great change of fortune, happening to kings, princes, and personages of great quality and dignity, whose reversals, deaths, misfortunes, and dangers arouse terror and compassion and cure and purify souls from these and other passions, serving as an example and lesson to all.” Thus, the radical shift in situation that occurs on stage is inherently dramatic. It seems to me that not a few of Scarlatti’s sonatas may refer to a similar model of unexpected and total reversal, which can concern harmony, rhythm, or the contrast of affect.

However, Spanish drama possessed an additional element of originality in its repertoire: the “Comedias de las Indias,” plays set in the New World and populated by its inhabitants. La palabra dada a los reyes y gloria de los Pizarro by Luis Vélez de Guevara and El Aurora a Copacabana by Pedro Calderón de la Barca are merely the two most famous titles. At the beginning of the 18th century, works of this kind had not yet integrated, let alone elaborated upon, the bloody drama with which the Hispanic nation had stained itself in relation to indigenous populations. Nevertheless, the wide circulation of historical works by indigenous chroniclers such as Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, Garcilaso de la Vega (El Inca), and Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti contributed to fueling the dramatic nature of these events in popular culture.

It is worth considering whether, and to what extent, such dramas of distant lands may have left an exotic imprint on the sonatas we will examine. More generally, it seems appropriate to note that the established widespread presence of Hispanisms/Iberisms in the musical language of the Sonatas does not exempt us from seeking the reflection and echo of other exoticisms within them, which were equally relevant in the cultural context where these works gestated. And I include in this category the many other forms of musical exoticism that early eighteenth-century melodrama experimented with, not only in the Italian vein but also, and with very original results, in the French one. Such research, I believe, is particularly imperative, but also rich in practical implications, from the perspective of transposing the Sonatas to the harp, whose idiom was widely employed throughout the 18th century precisely because of its evocative power for exotic, fantastic, and antiquarian scenarios. Consider, purely as an example, the function and context of the harp’s employment in Handelian literature: Giulio Cesare, Saul, Judas Maccabaeus, and the context of the concerto Op. 4 No. 6.

IL TEATRO SPAGNOLO

E parlando di teatralità non possiamo che immaginare, ora si, l’impatto del teatro spagnolo sul figlio del più celebre operista della sua epoca. Nel teatro spagnolo del XVIII secolo vivevano ancora tanto l’eclettica spontaneità di Lope de Vega quanto l’intensità drammatica di Pedro Calderòn de la Barca. Il trattatista Ignacio de Luzàn, nella sua monumentale Poética o reglas de la poesía pubblicata nel 1737, così definisce la tragedia: “Una rappresentazione drammatica di un grande mutamento di fortuna, accaduto a re, principi e personaggi di grande qualità e dignità, i cui rovesci, morti, disgrazie e pericoli suscitino terrore e compassione e curino e depurino le anime da queste e altre passioni, servendo da esempio e lezione a tutti.” Pienamente drammatico è quindi il radicale mutamento di situazione che avviene in scena. Non poche sonate di Scarlatti, mi pare, possono rifarsi ad un simile modello di inatteso e totale capovolgimento, che può riguardare l’armonia, il ritmo, il contrasto di affetto.

Ma il dramma spagnolo aveva nelle sue corde un ulteriore elemento di originalità: le “Comedias de las Indias”, cioè opere teatrali ambientate nel Nuovo mondo e popolate dai sui abitanti. “La parola data ai re e gloria dei Pizarro” di Luis Vélez de Guevara, e “L‘Aurora a Copacabana” di Pedro Calderón de la Barca sono giusto i due titoli più celebri. All’inizio del secolo XVIII le opere di questa sorta non avevano ancora integrato, né tantomeno elaborato, il dramma sanguinario di cui la nazione ispanica si era macchiata nei confronti delle popolazioni autoctone, tuttavia la larga circolazione delle opere storiche di cronisti indigeni Felipe Guamàn Poma de Ayala, Garcilaso de la Vega (El Inca), e Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti contribuivano ad alimentare nella cultura popolare la drammaticità di queste vicende.

Vale la pena chiedersi se, e in quale misura, tali drammi di terre lontane possono aver lasciato un’esotica impronta sulle sonate di cui ci occuperemo. Più in generale mi pare opportuno rilevare che l’acclarata estesa presenza di ispanismi-iberismi nel linguaggio musicale delle Sonate non ci esime dal ricercarvi il riflesso e l’eco di altri esotismi, tanto rilevanti nel contesto culturale in cui queste opere ebbero la loro gestazione. E includo in questa categoria le molte altre forme di esotismo musicale che il melodramma di inizio settecento sperimenta non solo nel filone italiano, ma anche, e con esiti molto originali, in quello francese. Tale ricerca credo sia particolarmente doverosa, ma anche ricca di ricadute pratiche, nella prospettiva di una trasposizione delle Sonate all’arpa, il cui idioma è stato largamente impiegato lungo tutto il XVIII secolo proprio in quanto evocativo di scenari esotici, fantastici, antiquari. Pensiamo, solo a titolo di esempio, alla funzione e al contesto dell’impiego dell’arpa nella letteratura Haendeliana: Giulio Cesare, Saul, Giuditta, e il contesto del concerto op. 4 n.6.

A Harp in the Theater of History

In the extensive analytical literature on Scarlatti’s works, considerable effort has been dedicated to identifying allusions to and imitations of guitars, wind instruments, and bells. We’ll soon address the concept of “instrumental vocalism” encapsulated by the term “cantabile.”

However, to date, no one has investigated the potential imitative idiomatic traces of the harp within the Sonatas. Yet, the harp was a widely diffused instrument in Spain during those years. Payment records from musical chapels in Spain and its directly subject provinces demonstrate the extensive use of the instrument at least until the mid-18th century. Treatises and instrumental literature dedicated to the harp in Spain reveal certain characteristics of performance practice that, in my judgment, can be found in some sonatas. In at least two letters from his immense epistolary (I say “at least,” because in my very incomplete reading of the corpus, I haven’t identified more), Farinelli recounts having heard a harp. What kind of harp was it? A Spanish arpa de dos órdenes or a French harp? Furthermore, Louise Élisabeth played the harp, and it’s difficult to imagine that she, who brought French instruments and music to Parma, would have been without one in Madrid. But beyond Louise Élisabeth, it seems rather strange that the significant penetration of French musical taste into the Spanish artistic scene of the third, fourth, and fifth decades of the century would not have included the French harp.

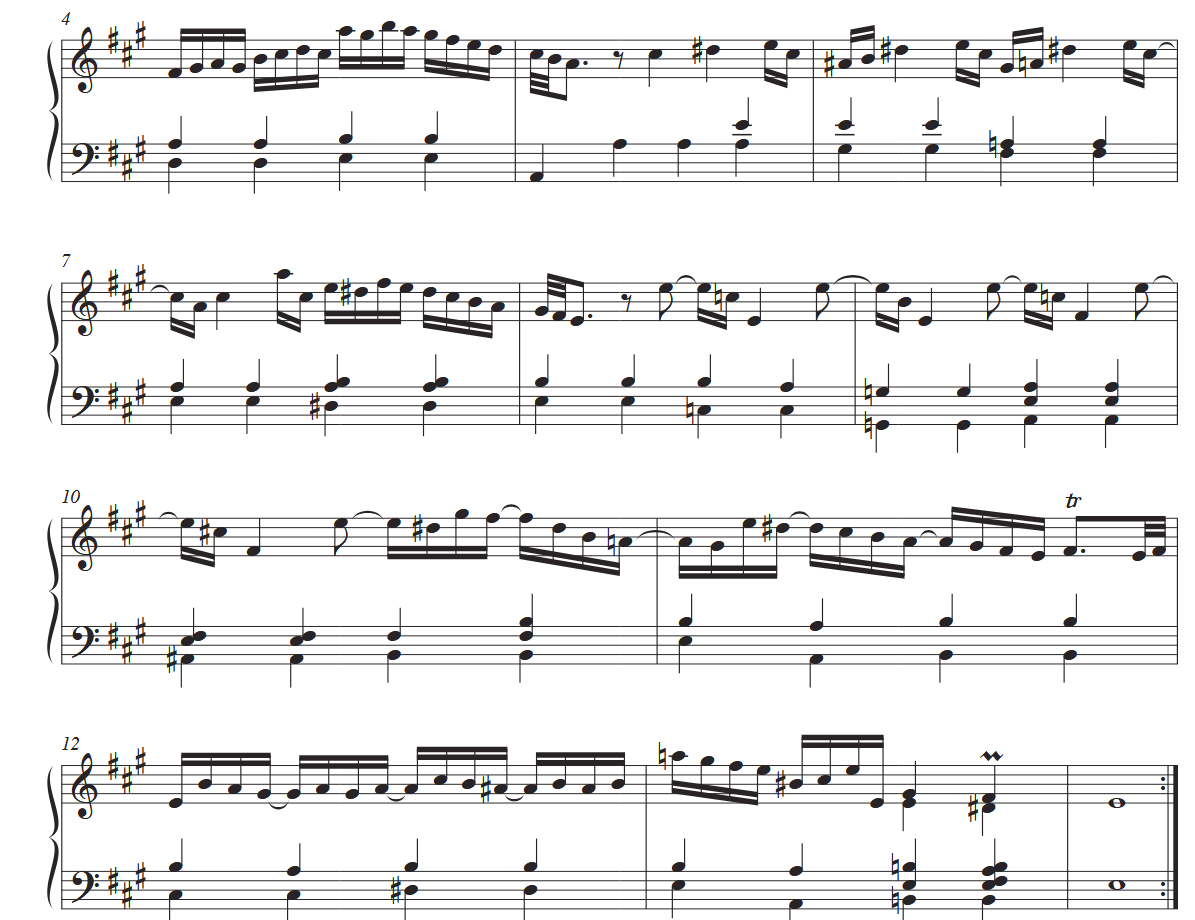

When I speak of the “French harp,” it’s important to note that a “French harp” existed before the “French harp”—that is, before the instrument characterized by its specific aesthetics and mechanism that would dominate French taste for over sixty years. The mechanical harp was, in fact, grafted onto an already consolidated practice of non-mechanical harps in France. F. Couperin’s “La harpée” offers a clear idea of the instrument’s sonic aura, and if you examine the texture of the piece, you’ll recognize an idiom employed multiple times by Scarlatti. Athénaïs de Montespan was famously portrayed by Caspar Netscher with a small harp on her lap; beside her, a lute, and one of her many children, still a child, playing a guitar. The French harp before the “French harp” was associated with lutes and guitars, not with keyboard instruments. Moreover, the first clear literary testament to the use of keyboard music on the French harp is precisely what initiated all our work: the famous passage from the memoirs of Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis. “Since there was nothing printed for the harp except a few trifles by Gaiffre, I began to play harpsichord pieces, and soon progressed to the most difficult: pieces by Mondonville and Rameau, and subsequently Scarlatti, Alberti, Handel, etc…” In 1759, the Sonatas transitioned from the keyboard to the string (harp), but I find intriguing the hypothesis that two or three decades earlier, some elements of a different harp idiom might have transitioned from the string to the keyboard. The opening of Sonata K 33 seems to propose, in succession, three typical forms of the harp idiom as depicted in the work of Torres and early French treatise writers: the arpeggio from the harmonic bass, the alternating-note arpeggio (in this case, descending), and the ascending and descending arpeggio.

UN’ARPA NEL TEATRO DELLA STORIA

Nella vasta letteratura analitica del testo scarlattiano si è molto lavorato sull’identificazione dei richiami e delle imitazioni di chitarre, strumenti a fiato, campane.

Della “vocalità strumentale” compresa dalla categoria “cantabile” avremo modo di occuparci tra poco.

Nessuno però, ad oggi, si è interrogato sulle possibili tracce idiomatiche imitative dell’arpa nelle Sonate. Eppure l’arpa era uno strumento diffusissimo in Spagna in quegli anni. I pagamenti delle cappelle musicali in Spagna e in molte province ad essa direttamente soggette hanno dimostrato l’uso estesissimo dello strumento fino almeno alla metà del secolo XVIII. I trattati e la letteratura strumentale dedicata allo strumento in Spagna ci rimandano alcune caratteristiche della prassi esecutiva che, a mio giudizio, sono riscontrabili in alcune sonate. In almeno due lettere del suo sterminato epistolario (dico “almeno”, perché nella mia lettura molto incompleta del corpus non ne ho individuate di più) Farinelli racconta di aver sentito un’arpa. Di che arpa si trattava? Arpa de dos ordenes o arpa francese? D’altronde Luisa Elisabetta suonava l’arpa, ed è difficile pensare che proprio lei, che portò a Parma strumenti e musica francesi, ne fosse sprovvista a Madrid. Ma al di là di Luisa Elisabetta parrebbe piuttosto strano che la sensibile penetrazione del gusto musicale francese nella scena artistica spagnola del terzo, quarto e quinto decennio del secolo non includesse l’arpa francese.

Quando parlo di “arpa francese” mi pare opportuno rilevare che esiste un’arpa francese prima dell’”arpa francese”, prima cioè dello strumento caratteristico per estetica e meccanica che dominerà il gusto francese per oltre sessant’anni. L’arpa munita di meccanica si innesta infatti, in Francia, sulla prassi già consolidata di arpe senza meccanica. “La harpée” Di F. Couperin ci dà una chiara idea dell’aura sonora dello strumento, e se date un’occhiata alla tessitura del testo riconoscerete un idioma impiegato più volte da Scarlatti. Athénais de Montespan fu ritratta da Caspar Netscher con una piccola arpa in grembo; accanto a lei un liuto, e uno dei molti figli, ancora bambino, che suona la chitarra. L’arpa francese prima dell’”arpa francese” era associata ai liuti e alle chitarre, non agli strumenti a tastiera. E d’altronde la prima chiara testimonianza letteraria dell’impiego di musica tastieristica sull’arpa francese è proprio quella da cui tutto il nostro lavoro ha preso le mosse: il famoso passo delle memorie di Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis. “Poiché per l’arpa non c’era nulla di stampato se non alcune cosette di Gaiffre, io mi misi a suonare dei pezzi per clavicembalo, e ben presto giunsi ai più difficili: i pezzi di Mondonville e di Rameau, e successivamente di Scarlatti, di Alberti, di Haendel ecc…”. Nel 1759 le Sonate dalla tastiera passano alla cordiera, ma trovo stimolante l’ipotesi che due o tre decenni prima qualche elemento di un diverso idioma arpistico dalla cordiera sia passato alla tastiera.

L’esordio della Sonata K 33 pare proporre una di seguito all’altra tre forme tipiche dell’idioma arpistico come è raffigurato nell’opera di Torres e nei primi trattatisti francesi: L’arpeggio dal basso d’armonia, l’arpeggio a note alternate ( in questo caso discendente) e l’arpeggio che sale e ridiscende):

Echoes of 18th-Century Vocalism

The final reflection of Spanish theater in Scarlatti’s time comes from the court theater, which developed along three thematic lines: mythology, fantastic novellas, and history. At the beginning of the 18th century, performances of Calderón’s works like “Eco y Narciso,” “El hijo del sol Faeton,” and “Apollo e Dafni” (drawn from Ovid’s narratives), along with “El monstruo del los Jardines” and “Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo,” were still frequent at court. Despite being half a century old, these works continued to fascinate the court. Fantastic, mythical, and magical are categories that, in my opinion, deserve to be explored within the indistinct “sense of wonder” that critics attribute to Scarlatti’s work. However, just as court theater in those very years gradually yielded to the seduction of French taste first, and then to the hegemony of Italian theater, it doesn’t seem out of place to ask whether this tension, this inexorable metamorphosis, is mirrored in the music we find on the music stand.

We’ve already discussed how Farinelli’s arrival in Madrid changed the fate of the Spanish monarchy. His influence inevitably left an indelible mark on the musical scene. Already under the direction of Annibale Scotti, court spectacles had become inexorably Italianized. The reconstructed Teatro de los Caños del Peral became the temple of Italian melodrama. Within a few years, Calderón’s musical dramas were mere memories. The reign of Ferdinand VI and Maria Barbara, inaugurated on October 10, 1746, was dubbed by Kirkpatrick “The Kingdom of Melomanes.” The Parmese Scotti handed over the direction of court spectacles to Carlo Broschi. Hasse, Galuppi, Jommelli, Mele… were the composers Farinelli commissioned for the court theater; Peruzzi, Uttini, Mingozzi, Elisi, Raaf, Caffarelli, Manzuoli, Panzacchi were the vocal stars hired without regard for expense; Luca Giordano frescoed the Cason del Coliseo; Jacopo Amiconi (who had already drawn the design for the frontispiece engraving of Essercizi) was called upon to handle the scenography, and after his death, the task passed to Antonio Jolli and Francesco Bataglioli. The marvelous world of 18th-century vocalism still flows clearly from the pages of the Sonatas: it’s a siren song that continues to seduce anyone who ventures into these oceans of music today.

As just one example among many, I’ll cite K 208, where I believe I can identify the main forms of vocal ornamentation. The written notes convey the uninterrupted flow of messanze, circuli, cercar della nota, morae vocis, whose free and undulating movement is superimposed on a bass line of quarter notes that relentlessly follows its own course.

L’ultimo riflesso del teatro spagnolo al tempo di Scarlatti viene dal teatro di corte, che si sviluppa su tre direttrici tematiche: mitologia, novellistica fantastica e storia. All’inizio del secolo XVIII sono ancora frequenti a corte le rappresentazioni delle opere di Calderòn “Eco y Narciso”, “El hijo del sol Faeton” “Apollo e Dafni”, riprese dalle narrazioni di Ovidio, e ancora “El monstruo del los Jardines”, “Fortunas de Andròmeda y Perseo”, che pur avendo compiuto il mezzo secolo ancora affascinavano la corte. Fantastico, mitico e magico sono categorie che, a mio avviso, meriterebbero di essere ricercate nell’indistinto “senso di meraviglia” che la critica attribuisce all’opera scarlattiana. Ma così come il teatro di corte, proprio in quegli anni, cedeva gradualmente alla seduzione del gusto francese prima, e all’egemonia del teatro italiano poi, non mi pare fuori luogo chiederci se questa tensione, questa inesorabile metamorfosi, trovi rispecchiamento nella musica che abbiamo sul leggio.

Abbiamo già parlato di come l’arrivo di Farinelli a Madrid cambiò le sorti della monarchia spagnola. La sua influenza non poteva non imprimere un’impronta indelebile alla scena musicale. Già sotto la direzione di Annibale Scotti gli spettacoli di corte si erano inesorabilmente italianizzati. Il ricostruito Teatro de los Canos del Peral divenne il tempio del melodramma italiano. In pochi anni dei drammi in musica di Calderòn restò solo il ricordo. Il regno di Ferdinando VI e Maria Barbara, inaugurato il 10 ottobre 1746, viene definito da Kirkpatric “Il regno dei melomani”. Il parmigiano Scotti lasciò a Carlo Broschi la direzione degli spettacoli di corte. Hasse, Galuppi, Jommelli, Mele …. gli autori che Farinelli chiamò a comporre per il teatro di corte; Peruzzi, Uttini, Mingozzi, Elisi, Raaf, Caffarelli, Manzuoli, Panzacchi le star canore scritturate senza badare a spese; Luca Giordano affresò il Cason del Coliseo; Jacopo Amiconi ( che già aveva tracciato il disegno da cui fu tratta l’incisione per l’antiporta di Essercizi) fu chiamato ad occuparsi delle scenografie, e dopo la sua morte l’incarico passò ad Antonio Jolli e Francesco Bataglioli. Il meraviglioso mondo della vocalità settecentesca sgorga ancora limpido dalle pagine delle Sonate: è un canto di sirena che seduce ancora oggi chi si avventura in questi oceani di musica.

Solo come esempio, tra i tanti, citerò K 208 dove mi pare di poter ritrovare le principali forme di ornamentazione vocale. Le note scritte rendono il flusso ininterrotto di messanze, circuli, cercar della nota, morae vocis il cui andamento libero e ondivago è sovrapposto ad un basso di semiminime che segue implacabilmente il proprio corso.

The Theater of Art and Its Characters

Returning for a moment to Enrico Baiano’s profound insight into the theatricality of Scarlatti’s Sonatas, and taking it seriously as a hermeneutical method for the musical texts we are studying, it seems necessary to take another step back from our current level of analysis. Let’s try to move from understanding Spanish theater to the broader universe of 17th and 18th-century theater. This subject is vast and complex, and I am certainly not an expert. Yet, consider Carlo Goldoni’s La Locandiera, or Beaumarchais’s The Barber of Seville, or even Pedro Antonio de Alarcón’s The Three-Cornered Hat, which is inspired by 18th-century Spanish popular theater (you might know it from Manuel de Falla’s ballet, but there was also a 1950s film with Sophia Loren on the same subject, I believe titled La bella mugnaia). Italian comedy of those years drew extensively from 18th-century theater precisely because it offered a clear, universally understandable, stereotypical, yet not obvious, model. For now, let’s limit our discussion to comedy or mezzo carattere, as tragedy would lead us too far afield.

These plays, even before telling a story, bring characters to the stage. Not by chance, in Anglo-Saxon countries, a theatrical personage is called “the character.” Have you ever found yourself reflecting that Don Pasquale from Donizetti’s opera is theatrically quite similar to Don Bartolo from The Barber of Seville? And that Don Basilio from the latter and Doctor Malatesta from the former share more than one common trait? And that Norina and Adina from L’elisir d’amore have more than just their names to connect them? A true melomane would tell us we understand nothing, but trust me, the crux lies precisely in the stereotyping of the character, that is, in its characterization. And the clearer and more recognizable the character, the more the composer’s originality can be poured into it, without risking confusing the audience.

However, the world of art knows characters far more complex than the old miser, the tedious doctor, the flirtatious young woman, or the somewhat dull lover. Think of the modern commedia dell’arte of Eduardo de Filippo and the complexity of his characters. Now think about music. Not just Scarlatti’s. Can music express these characters without words, without facial expressions? Without stage action? This question is directly answered by a vast compositional genre known as “pièces de caractère,” which had its golden age in 18th-century France. These are short compositions, each musically portraying a character that we might define as scenic or theatrical. Most often, they bear a person’s name: La Princesse de Sens, La Cottin, La Ferrande, La Forqueray; Petrini writes La Pauline. A portrait in music. Don’t you find it a fascinating challenge to reconstruct the character of someone we haven’t met, having only the music on the stand at our disposal? I find it an extraordinary exercise. Others bear names of categories, ethnicities, or atmospheres: L’Egyptienne, La portugaise, La basque, or musical instruments: La harpée, La mandoline. But what directly interests us now is the immense repertoire of human characters: L’indiscrète, La timide, L’insinüante, La triomphante, La séduisante, La distraite… a true theater of humanity. Harpsichord literature also owes much to this genre: think of La fierre, La Riverie, La Bavarde, La Villageoise by Hinner. A large portion of the output by Petrini, Cardon, and La Maniere can also be traced back to pièces de caractère, even without bearing the title. And the allusions between one character and another are delightfully elusive. Musical portraits can be a tribute, but also a caricature; a bow or a mocking smile. Read this literature. You will find many common elements with the Sonatas. And you will never be able to say who influenced whom, assuming it is even that important to establish in music, and especially if it is philologically possible to do so with certainty. Read Jacques Duphly’s La Cazamajor. You can hear Scarlatti. With a French accent, but it truly sounds like Scarlatti. A tribute? An echo? Scholars say many things. I cannot say. But if you like the genre, put it on your music stand: it works exquisitely on the harp.

In short: 18th-century music is music of affections, and this, at least in theory, we know, but sometimes we forget that it is also music of character. And the two dimensions have a complex relationship. It is my firm conviction that we must look at this vast literature with attention and interest, not only to better understand the compositional intention behind a large portion of Scarlatti’s work, but also to form a lexicon, a thesaurus, a true dictionary of 18th-century musical discourse which, in its instrumental form, may not be obvious or immediately comprehensible to the contemporary performer. The 18th-century sonata repertoire for harp drew heavily from this literature. Does this relate to our Sonatas? To the one I have on my music stand? If, as I believe, these works, as a whole, are a mirror of the culture in which they were conceived and of the genius of their author, then I believe that those scenographies, those paintings, those stagings must necessarily be reflected in them; in them, those many musical discourses, and those many different ways of vocalizing, of positioning the voice, of astonishing and enchanting the audience, must somehow echo.

And this work of exploration, this search for the climate, the cultural atmosphere, this immersion in the artistic context, we owe not only to Domenico Scarlatti: we owe it to every author we engage with. We owe it to our art and our professionalism because, in my judgment, it is largely through this that the distinction between a cultural professional and an entertainment professional is drawn.

IL TEATRO DELL’ARTE E I SUOI CARATTERI

Tornando ancora per un momento alla profonda intuizione di Enrico Baiano sulla teatralità delle Sonate, e prendendola sul serio come metodo ermeneutico dei testi musicali che stiamo studiando, mi sembra necessario fare ancora un passo indietro rispetto al piano di analisi fin qui frequentato. Proviamo a passare dalla comprensione del teatro spagnolo al più ampio universo del teatro del XVII e XVIII secolo. La materia è vasta, complessa ed io non ne sono certo uno studioso. Ma pensate alla Locandiera di Carlo Goldoni, o al Barbiere di Siviglia di Beaumarchais, o ancora al Cappello a tre punte di Pedro Antonio de Alarcòn, che si ispira proprio al teatro popolare spagnolo del XVIII secolo (magari lo conoscete per il balletto di Manuel de Falla, ma c’era anche un film degli anni ’50 con Sofia Loren sullo stesso soggetto. Credo si intitolasse “La bella mugnaia”. La commedia italiana di quegli anni si servì a piene mani dal teatro del settecento, proprio perché era un modello chiaro, comprensibile a tutti, stereotipato, ma non ovvio). Limitiamo per ora il discorso alla commedia o al mezzo carattere, perché la tragedia ci porterebbe lontano. Queste opere teatrali, prima ancora che una storia, portano in scena dei personaggi. Dei caratteri. Non a caso nei paesi anglosassoni il personaggio teatrale è “the caracter”. Vi siete mai sorpresi a riflettere che don Pasquale, dell’opera di Donizetti, è teatralmente assai simile a don Bartolo del Barbiere di Siviglia? e che il don Basilio di quest’ultima e il dottor Malatesta della prima hanno più di un tratto in comune? E che Norina e Adina dell’Elisir d’amore hanno più che il nome ad accostarle? Un melomane che si rispetti ci direbbe che non capiamo nulla, però fidatevi che il nodo sta proprio nella stereotipazione del carattere, cioè nella sua caratterizzazione. E più è chiaro e riconoscibile il carattere, più l’originalità del compositore potrà riversarvi sopra la propria creatività, senza correre il rischio di confondere lo spettatore.

Ma il mondo dell’arte conosce caratteri ben più complessi del vecchio avaro, del dottore noioso, della giovane civettuola, dell’innamorato un po’ tonto. Pensate alla moderna commedia dell’arte di Eduardo de Filippo e alla complessità dei suoi caratteri. Pensate ora alla musica. Non solo a quella di Scarlatti. La musica può esprimere questi caratteri senza parole, senza mimica facciale? Senza un’azione scenica? A questa domanda risponde in modo diretto un vasto filone compositivo che va sotto il nome di “pieces de caractere” e che ebbe la sua stagione d’oro in Francia nel secolo XVIII. Si tratta di brevi composizioni ognuna delle quali ritrae musicalmente un carattere che potremmo definire scenico o teatrale. Il più delle volte hanno il nome di una persona: La Princesse de Sens, La Cottin, La Ferrande, La Forqueray; Petrini scrive La Pauline. Un ritratto in musica. Non vi pare una bella sfida ricostruire il carattere di una persona che non abbiamo conosciuto avendo a disposizione solo la musica sul leggio? Io lo trovo un esercizio straordinario. Altri hanno nomi di categorie, etnie, atmosfere: L’Egyptienne, La portugaise, La basque, o di strumenti musicali: La harpée, La mandoline. Ma quello che adesso ci interessa direttamente è lo sterminato repertorio dei caratteri umani: L’indiscrete, La timide, L’insinüante, La triomphante, La séduisante, La distraite… un vero teatro dell’umanità. Anche la letteratura arpistica deve moltissimo al genere: pensate a La fierre, La Riverie, La Bavarde, La Villageoise, di Hinner. Ma una larga fetta della produzione di Petrini, Cardon, La Maniere è riconducibile ai pieces de caractere, pur non portandone il titolo. E i richiami tra un carattere e l’altro sono deliziosamente sfuggenti. I ritratti in musica possono essere un omaggio, ma anche una caricatura; un inchino o un sorriso di scherno. Leggete questa letteratura. Ci troverete tanti elementi comuni con le Sonate. E non saprete mai dire chi ha influenzato chi, ammesso che poi in musica sia poi così importante stabilirlo, e soprattutto che sia filologicamente possibile farlo con certezza. Leggete La Cazamajor di Jacques Duphly. Si sente Scarlatti. Con l’accento francese, ma pare proprio Scarlatti. Un’omaggio? Un eco? Gli studiosi dicono tante cose. Io non so dire. Ma se vi piace il genere mettetela sul leggio: all’arpa funziona squisitamente.

Insomma: la musica del settecento è musica degli affetti, e questo, almeno in teoria, lo sappiamo, ma a volte scordiamo che essa è anche musica di carattere. E le due dimensioni hanno un rapporto complesso. E’ mia convintissima opinione che a questa vasta letteratura dobbiamo guardare con attenzione e interesse non solo per meglio comprendere l’intenzione compositiva di una vasta porzione dell’opera scarlattiana, ma per formarci un lessico, un tesauro, un vero e proprio dizionario del discorso musicale settecentesco che, nella sua forma strumentale, può non risultare ovvio e immediatamente comprensibile all’esecutore contemporaneo. Il repertorio sonatistico del settecento per arpa attinse a piene mani da questa letteratura. Ha a che fare questo con le nostre Sonate? Con quella che ho sul leggio? Se, come io credo, queste opere, nel loro complesso, sono lo specchio della cultura in cui sono state concepite e del genio del loro autore, allora io penso che in esse debbano per forza specchiarsi quelle scenografie, quei dipinti, quelle messe in scena; in esse devono in qualche modo echeggiare quei tanti discorsi musicali, e quei tanti diversi modi di vocalizzare, di porre la voce, di stupire e incantare il pubblico.

E questo lavoro di esplorazione, questa ricerca del clima, dell’atmosfera culturale, questa immersione nel contesto artistico non la dobbiamo solo a Domenico Scarlatti: la dobbiamo ad ogni autore con cui ci confrontiamo. La dobbiamo alla nostra arte e alla nostra professionalità perché, a mio giudizio, è in larga misura da qui che passa la distinzione tra un professionista della cultura e un professionista dell’intrattenimento.

(Lorenzo Montenz)