di Elisabeth Plank

(traduzione a cura di Gilda Gianolio)

La Sonata per arpa di Paul Hindemith è uno delle composizioni più importanti della letteratura arpistica e, nonostante abbia ormai quasi settantasette anni, ancora porta a numerosi diverbi.

Avendo studiato l’autografo della Sonata di Hindemith per la mia tesi, ed essendo stata la prima a trascrivere la corrispondenza dell’autore con Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi, vorrei condividere alcuni approfondimenti che ho sviluppato grazie alla mia ricerca, e contribuire allo scambio di opinioni sulla Sonata anche fornendo nuovi spunti.

Ho basato la mia ricerca sugli autografi e le lettere conservate all’”Hindemith Institute” di Francoforte e sull’interpretazione di Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi, giunta a noi grazie ai suoi numerosi studenti. Avendo lavorato con Elena Zaniboni sulla Sonata, ovviamente concordo col suo articolo – tranne su un punto sul quale ci eravamo già rese conto di essere in disaccordo.

Descrizione: storia e struttura

Analizzare un brano da diverse angolazioni aiuta sempre a comprenderlo e quindi impararlo. Ci sono vari aspetti da considerare: un’analisi formale aiuta a a memorizzarlo e a dargli una struttura. L’interpretazione a volte può essere basata, come in questo caso, sul background, sulla biografia del compositore e sulla storia del brano stesso. Questo può essere utile per capire le emozioni che un pezzo dovrebbe trasmettere.

La “Sonata per arpa” di Paul Hindemith fa parte di un ciclo di sonate composte tra il 1935 e il 1955, per un totale di ventisei brani per vari strumenti.

Uno dei motivi per i quali l’autore compose queste sonate fu la situazione politica dell’epoca. Dopo che ebbe apertamente criticato il regime tedesco in Svizzera nel 1934, i suoi lavori non furono più divulgati in Germania e nacque un’ostilità nei suoi confronti. Dal 1936 in poi le esecuzioni delle composizioni di Hindemith furono vietate e gli fu negato di lasciare il paese per dare concerti all’estero (nonostante fosse un violista virtuoso e molto impegnato). In quel periodo, il compositore si concentrò di conseguenza nella scrittura dei suoi trattati teorici. I brani che compose in quegli anni (molti Klavierlieder, “Mathis del Mahler”) mostrano quanto fosse provato dalla situazione. Poiché non poteva lasciare il paese per le sue attività concertistiche, suonava molti duetti con sua moglie in casa, e poiché aveva abbastanza materiale, compose alcune delle sonate.

Nel 1938 la coppia emigrò in Svizzera, dove Hindemith compose la “Sonata per arpa”.

Il terzo movimento della Sonata è come una canzone senza le parole. L’atmosfera e la storia raccontati nella poesia sono importanti per la comprensione dell’intero brano. Presumibilmente, Hindemith fornì una descrizione della Sonata: il primo movimento descrive la chiesa, dove sta provando un organista, il secondo movimento parla del bambino che gioca, correndo e cantando davanti alla chiesa, e l’ultimo movimento parla della morte e della commemorazione del defunto. (Pöschl-Edrich p.22; Carl Swanson disse che forse il suo maestro Pierre Jamet gli raccontò questa storia).

Questo vorrebbe dire che parti della poesia sono rese in musica anche negli altri due movimenti e non solo nel terzo.

La scelta della poesia è inusuale per Hindemith. In altri lavori preferiva scrittori contemporanei, mentre questa poesia è di Ludwig Cristoph Heinrich Hölty (1748-1776), poeta del diciottesimo secolo. È molto probabile che lo scoppio della seconda guerra mondiale (1 settembre 1939) abbia influenzato il lavoro e la scelta della poesia , così come a un movimento (Trauermusik) della sua sonata per tromba (Natale 1939) è associata la poesia “Alle Menschen müssen sterben” (tutti gli uomini devono morire).

Come una sonata classica, la “Sonate für Harfe” consiste in tre movimenti:

-

Mäβig schnell

-

Lebhaft

-

Lied – Sehr langsam

Anche se è descritto come “moderatamente veloce”, il primo movimento è lento la maggior parte del tempo. È un ibrido tra una forma sonata e un rondò (Pöschl-Edrich, Barbara: Modern and tonal: An analytical study of Paul Hindemith’s Sonata for Harp;Dissertation – Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts.

Boston University College of Fine Arts, 2005: p. 58)

|

Sezione |

Suddivisione |

Misure |

|---|---|---|

|

Esposizione |

A – B – A’ |

1 – 56 |

|

Sviluppo |

C |

57 – 76 |

|

Ripresa |

A” – B’ – A”’ |

77 – 124 |

Il secondo movimento è una forma sonata

(Plank, Elisabeth: Die Harfenistin Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi und ihre Zusammenarbeit mit Paul Hindemith un Alfredo Casella. – Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor o Musical Arts. Boston University College of Fine Arts, 2005: p.39)

|

Sezione |

Temi |

Misure |

|---|---|---|

|

Esposizione |

Primo tema, secondo tema |

1 – 36 |

|

Sviluppo |

Primo tema, nuovo materiale |

37 – 116 |

|

Ripresa |

Primo tema, secondo tema |

117 – 165 |

|

Coda |

Frammento del primo tema |

166 – 171 |

Il terzo movimento è un Lied in tre versi

|

Sezione |

Misure |

|---|---|

|

Primo verso |

1 – 10 |

|

Secondo verso |

11 – 20 |

|

Terzo verso |

21 – 32 |

La struttura e il ritmo (Pöschl-Edrich p.22; This has been reported by Carl Swanson. He said, that maybe his teacher Pierre

Jamet told him this story.) del terzo movimento corrispondono facilmente con le parole della poesia. Per questa ragione e a causa dell’argomento della poesia, il tempo fornito sembra troppo veloce, soprattutto considerando l’indicazione “Sehr langsam” (molto lento).

Un altro motivo per cui Hindemith compose il ciclo di sonate fu per dimostrare le teorie che aveva sviluppato in “Unterweisung im Tonsatz” (arte della composizione musicale). Il primo motivo della sonata, Urmotiv, (si bemolle – mi bemolle – re bemolle; quarta ascendente, seconda discendente) può essere trovato nell’intero lavoro in varie forme (invertite, retrograde), ad esempio all’inizio del terzo movimento (re bemolle – si bemolle – mi bemolle). Inoltre, gli stessi centri tonali dei movimenti sono un’inversione retrograda dell’Urmotiv: I movimento: sol bemolle, II movimento: la bemolle, III movimento: mi bemolle.

Un’altra caratteristica della musica di Hindemith è l’uso frequente di quarte e quinte parallele, e il primo tema del primo movimento ne è un esempio lampante (si bemolle – mi bemolle, re bemolle – sol bemolle, … re bemolle … la bemolle, si bemolle – fa). (Bruhn, Siglind: Hindemiths groβe Instrumentalwerke. Waldricht: Edition Gorz, 2012 p.43)

Hindemith è un personaggio molto interessante. Ad esempio, era molto veloce; comporre la Sonata gli richiese solo due giorni, e la bozza è quasi identica alla versione stampata. Credeva che si dovesse comporre tutto d’un fiato: “[…] se non possiamo, nel lampo di un singolo momento, vedere una composizione nella sua assoluta interezza, con ogni dettaglio pertinente nel suo posto, non siamo creatori genuini.” (da: Hindemith, “A Composer’s World”, p.84 f); non era un compositore che “cercava” un pezzo per ore, seduto al pianoforte. Era anche sempre consapevole delle debolezze e delle forze di ogni strumento musicale.

Nel suo libro “A Composer’s World” elenca gli svantaggi dell’arpa, ad esempio il fatto che a volte manchi di fluidità e che il suono sia discontinuo, poiché il suono viene generato dalle dita. Il diretto contatto tra musicista e strumento e il fatto che l’arpa sia molto adatta agli accordi sono invece alcuni dei vantaggi che menziona.

La Sonata per arpa consiste in molti accordi e non ha la tipica scrittura virtuosistica, poiché i passaggi veloci sono usati più per creare ambienti sonori che per essere virtuosistici. Per Hindemith era essenziale capire uno strumento per essere capaci di comporre per esso. Sapeva suonare diversi strumenti (l’arpa è uno di quelli che non sapeva suonare), cosa che richiedeva anche ai suoi studenti.

Hindemith iniziò la sua carriera all’inizio come violinista alla Frankfurt Opera House, per poi diventare uno dei più grandi virtuosi di viola del suo tempo.

Traduzioni

Siccome le indicazioni in tedesco sugli spartiti non sono molto comuni e ho visto molti errori nelle traduzioni, ho deciso di fornire una traduzione di tutte le indicazioni in tedesco:

Mäβig schnell (pagina 3 riga 1 misura 1) – moderatamente veloce

Ruhig, ein wenig frei (5-2-1) – calmo, piuttosto libero (nell’edizione di Grandjany, “ruhig” è stato tradotto come tranquillo; può essere tradotto sia come “calmo” che come “tranquillo”. In questo contesto, essendo un’indicazione di tempo, significa calmo)

Verklingen (5-2-5) – sparendo, perdendosi

Neu beginnen (5-3-2) – cominciando di nuovo (non significa necessariamente tempo primo!)

Vorangehen (5-4-1) – accelerando

Zurückhalten und verklingen (5-5-2) – morendo

Im Hauptzeitmaβ (6-1-1) – tempo primo

Breit (7-1-1) – ampio

Im Hauptzeitmaβ (7-4-2) – tempo primo

Ruhiger (8-1-1) – più calmo

Langsam (8-4-1) – lento

Lebhaft (9-1-1) – vivamente

Hervor! (10-4-7) – in evidenza

Sehr langsam (14-1-1) – molto lento

Armonici e dinamiche

Elena Zaniboni ha già scritto sull’importanza delle armonici nella Sonata, ma devo menzionare di nuovo questo punto, perchè voglio indebolire le teorie che hanno portato per decenni a discussioni inutili.

Come Elena Zaniboni dice, ovviamente correttamente (avendo eseguito la Sonata per Hindemith stesso), gli armonici dovrebbero essere suonati sulla corda indicata. Sembra strano che, nonostante non vi possano essere dubbi a proposito del modo in cui gli armonici vadano suonati in questo brano, che ci siano ancora tante teorie e discussioni che circolano nel mondo dell’arpa.

Ci sono tre argomentazioni a favore del suonare gli armonici all’ottava inferiore:

– Carlos Salzedo ha usato questa notazione nel suo “Modern Study of the Harp” (1921), ed essendo un contemporaneo di Hindemith, qualcuno sostiene che debba aver adottato le sue teorie, ma Hindemith non possedette mai, né probabilmente vide mai, un’edizione del libro.

– un’altra argomentazione è la seguente riga della poesia: “The strings unbidden murmur like humming bees”: nella versione tedesca dice “Leise wie Bienenton”, che non si riferisce per nulla all’onomatopeico “buzz” (dice “il verso delle api”); comunque, il suono delle api potrebbe essere udito sia acuto che grave e non dovrebbe essere preso come un argomento a favore di un problema esecutivo.

– altri dicono che, siccome Hindemith scriveva gli armonici nelle sue composizioni violistiche nel modo citato, anche gli arpisti dovrebbero suonarli così. Hindemith si opporrebbe fermamente, perchè la Sonata è una composizione per arpa. Chiunque sia venuto in contatto con la persona e il lavoro di Hindemith, come detto precedentemente, sa che era per lui fondamentale studiare attentamente uno strumento prima di comporre per esso, quindi non avrebbe mai usato la notazione della viola per scrivere per arpa.

A parte il fatto più eclatante, cioè che Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi suonasse gli armonici sulla corda reale, c’è un altro argomento significativo di cui tener conto e cioè l’uso degli armonici in altri lavori di Hindemith (ad esempio “Drei Gesänge für Sopran und groβes Orchester op.9”, 1917, o “Konzertmusik für Klavier, Blechbläser und Harfen op.49”, 1930) per cui risulta chiaro che l’orchestrazione non permette la possibilità che siano suonati all’ottava inferiore.

Ahimè, la prima fonte di discussioni sulla Sonata è la dinamica nell’ultima riga del secondo movimento. C’è una prova scritta da Hindemith stesso che debba essere pp, pianissimo.

Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi diceva ai suoi allievi di suonare l’ultima riga fortissimo.

Nell’edizione del 2004 la dinamica scritta nell’ultima riga del secondo movimento è un forte, che non può essere giustificato. Nel primo autografo della Sonata (Erstschrift), nello stesso punto, si può trovare scritto fortissimo, ma nel secondo autografo, Reinschrift, è notato un pianissimo.

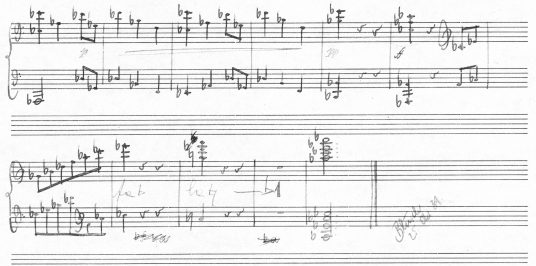

A2 picture 1: Example 1 – Erstschrift, Paul Hindemith: „Sonate für Harfe“, 2nd movement, mm. 162-172

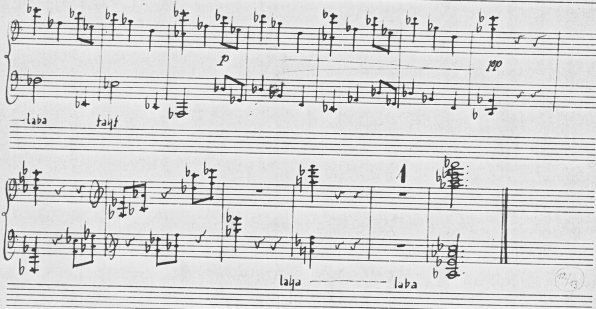

A2 picture 2: Example 2 – Reinschrift, Paul Hindemith: „Sonate für Harfe“, 2nd movement, mm. 166-172

Nell’opera di Hindemith, l’ultima versione è sempre quella valida. Questo significa che, invece che forte, dovrebbe essere pianissimo (come stampato nella prima edizione del 1940), errore che è stato corretto nelle ristampe fino ad oggi.

Ma com’è possibile che questo errore sia avvenuto?

La Sonata fu stampata nel febbraio del 1940 da Schott, nell’epoca in cui Hindemith si stava trasferendo negli U.S.A., dunque la stampa non fu mai corretta da lui (come invece fece con molte delle sue opere negli anni ’50). Una lettera di correzione scritta dal compositore (probabilmente) nel 1943 per AMP non menziona le dinamiche in questa parte.

Nel 1962 Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi, avendo sentito i concorrenti in Israele eseguire la Sonata, scrisse una lettera a Hindemith sulle dinamiche (lei scriveva tutte le sue lettere a Hindemith e a sua moglie in un francese spesso letteralmente tradotto dall’italiano; è riportato qui esattamente e senza correzioni):

“Pendant notre correspondence (dans le 1940) au sujet de la Sonate, Hindemith m’avait envoyer les épreuves d’imprimerie et les 6 dernières mesures du II mouvement etaients ff. Aussitôt publiée il n’y a rien écrit, ni ff ni pp. Et puisque avant ces 6 mesures il est signé p les interprètes jouent p. -[…] et moi, j’a toujours joué ff […] J’aimerai savoir ce que Hindemith aime, peût être avant la publication il a changé?”

“Dopo la nostra corrispondenza (del 1940) a proposito della Sonata, Hindemith mi mandò le prime stampe e le ultime sei misure del secondo movimento erano ff. Dopo che la Sonata fu pubblicata, non v’ era scritto nulla [lì]. Né un ff né un pp. Ed ora dice p, e per questo gli esecutori suonano p. -[…] E io ho sempre suonato ff. […] vorrei sapere cosa Hindemith preferisca, probabilmente ha cambiato il punto prima che l’opera fosse pubblicata.” – Lettera di Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi a Gertrud Hindemith, 9.9.1962.

Come risposta, Hindemith scrisse una nota sulla lettera:

“Ich weiβ nicht mehr, wie das Original war, glaube auber, daβ ich für die endgültige Drucklegung, die jetzt geläufige Form (also pp bleiben) gewählt hatte. Sie möge also bitte auf ihr Privat-ff verzichten”

“Non riesco a ricordare la versione originale, ma penso di aver optato, per la stampa, per la versione attuale (restare in pp). Vorrebbe essere così gentile da astenersi dal suonare la sua privata versione ff.”

Nel 1989 un’arpista tedesca chiamò gli editori della Schott e chiese loro di cambiare la ristampa successiva cambiando la dinamica da pianissimo a forte, perchè Hindemith stesso le aveva detto di suonare forte (Elena Zaniboni dice la stessa cosa. Una volta ebbe l’occasione di chiedere a Hindemith cosa ne pensasse, gli suonò entrambe le versioni e lui le disse che suonare forte era “bello!” da Planck, p.33).

Poi, a causa di un doppio errore, l’”Hindemith Institute” confermò il forte, basato sul primo autografo (anche se in quell’autografo Hindemith aveva scritto fortissimo). Il problema era che, fino ad allora, non era chiaro che il manoscritto in possesso della Schott fosse il secondo autografo; dunque nell’edizione del 2004 la dinamica fu cambiata (Plank, p.32f).

Qualsiasi fossero le sue intenzioni Hindemith era flessibile col suo lavoro e forse, quando gli fu chiesto, sul momento preferì il forte. Ma io penso che, volendo suonare sicuri di essere nel giusto, ci siano evidenze scritte perchè si suoni pianissimo e, come scrisse Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi:

“Je vous en priè, ecrivez moi le plus tôt possible, car je veux jouer exactement ce qu’il aime car la Sonate a eté dedié à moi et il serait tres curieux de ma part de la jouer… mal.”

“Vi chiedo gentilmente di rispondermi il più velocemente possibile, perchè voglio suonare esattamente come lui vuole, poiché la Sonata è stata dedicata a me e sarebbe strano da parte mia suonarla… male”.

Gli estratti degli autografi sono pubblicati per gentile concessione della “Fondation Hindemith”, Blonay (CH). Le fonti non pubblicate (lettere, autografi, cataloghi), se non scritto diversamente, sono conservate all’”Hindemith Institut” di Francoforte.

Grazie a Elisabeth Plank per averci inviato questo prezioso lavoro di ricerca e a Gilda Gianolio per la traduzione. Sono entrambe arpiste e ottime interpreti della Sonata per arpa di Paul Hindemith.

Articolo in lingua originale pubblicato dall’American Harp Journal che ringraziamo per la gentile concessione.

Elisabeth Plank

Paul Hindemith: “Sonate für Harfe”

-

historical background & practical aspects

Paul Hindemith’s “Sonate für Harfe” is one of the most important pieces of the harp literature and -being nearly seventy-seven years old- still leads to vivid discussions.

Having studied the autographs of Hindemith’s “Sonate für Harfe” for my thesis and being the first to transcribe the correspondence of Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi with Paul Hindemith, I wanted to share some of the insights I gained from my research and contribute to this exchange about the Sonata by also adding new input. I based my research on the autographs and letters kept in the “Hindemith Institut” in Frankfurt and the interpretation of Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi passed on through her many students. Having worked with Elena Zaniboni on the Sonata, I of course completely agree with her article, there is only one point on which we already have agreed to disagree.

Description: history and structure

Analysing a piece through various angles always helps with understanding, and thus, learning it. There are various aspects to consider: a formal analysis helps to learn it by heart and giving it a structure. Interpretation sometimes also can be based on analysis, in this case, looking into the background and the biography of the composer and the history of the piece. This can be helpful to understand the emotions a piece should transport. Paul Hindemith’s „Sonate für Harfe“ is part of a cycle of sonatas he composed from 1935 to 1955, of altogether twenty-six pieces for various instruments. One reason for composing the sonatas was the political situation during that time. After criticising the German regime openly in Switzerland in 1934, Hindemith’s works were not broadcasted in Germany anymore and hostility towards his person arose. From 1936 on performances of Hindemith’s works were banned and he would not get permission to leave the country to give concerts abroad.1 In that period, he focused on writing his theoretical works. Pieces he composed during that time (many Klavierlieder, “Mathis der Maler”) show how deeply he was affected by his situation. Because Hindemith wasn’t allowed to leave the country for his concertistic activities, he played lots of duets with his wife at home, and to have enough material, he composed some of the sonatas. In 1938 the couple emmigrated to Switzerland, where Hindemith composed the „Sonate für Harfe“.

The third movement of the Sonata is like a song without words. The atmosphere and the story told in the poem are important for the interpretation of the whole piece. Allegedly, Hindemith gave a description of the sonata:2 The first movement depicts the church, and an organ player is practising inside. The second movement is about the children playing, fighting and singing in front of the church, and the last movement is about death and commemoration of the dead. That means that parts of the poem are set to music in the other movements as well.

The choice of poetry is unusual for Hindemith. In other works he tended towards contemporary writers, whereas this poem is by 18th century poet Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty3. It is very likely, that the outbreak of the second world war (1st of September 1939) influenced Hindemith’s work and choice of poetry, one movement –Trauermusik (funeral music)- of his sonata for trumpet (Christmas 1939) is combined with a poem “Alle Menschen müssen sterben” (All Men have to die).4

Like a classical sonata, the „Sonate für Harfe“ consists of three movements:

I. Mäßig schnell

II. Lebhaft

III. Lied – Sehr langsam

Although it being described as “moderately fast”, the first movement is slow most of the time.

It is a hybrid of a sonata form and a sonata rondo.5

|

Section |

Part |

Measure |

|

Exposition |

A – B – A’ |

mm. 1 – 56 |

|

Development |

C |

mm. 57 – 76 |

|

Recapitulation |

A’’ – B’ – A’’’ |

mm. 77 – 124 |

The second movement is a sonata form6

|

Section |

Themes |

Measure |

|

Exposition |

First theme, second theme |

mm. 1 – 36 |

|

Development |

First theme, new material |

mm. 37 – 116 |

|

Recapitulation |

First theme, second theme |

mm. 117 – 165 |

|

Coda |

Fragment of the first theme |

mm. 166 – 171 |

The third movement is a Lied in three verses.

|

Section |

Measure |

|

1st verse |

mm. 1 – 10 |

|

2nd verse |

mm. 11 – 20 |

|

3rd verse |

mm. 21 – 32 |

The structure and rhythm7 of the third movement correspond easily with the spoken words of the poem. For this reason and because of the poem’s topic, the given tempo seems very high- especially with the marking “Sehr langsam” (Very slow).

Another reason why Hindemith composed the cycle of sonatas was to demonstrate the theories he developed in “Unterweisung im Tonsatz” (“Craft of Musical Composition”). The first motive of the sonata, Urmotiv, (b flat – e flat – d flat; ascending fourth, descending second) can be found in the entire work in various forms (inversion, retrograde) e.g. the beginning of the third movement (d flat – b flat – e flat). Also, the tonal centres of the movements are a retrograde-inversion of the Urmotiv: 1st movement: G flat, 2nd movement: A flat, 3rd movement: E flat.8

Another feature of Hindemith’s music is the frequent use of parallel fourths and fifths, the first theme of the first movement being a very prominent example (b flat – e flat, d flat – g flat, … d flat…a flat, b flat – f).9

The composer Hindemith is a very interesting character. For one reason, he was very quick; composing the Sonata took him two days, the draft of the Sonata being nearly identical with the printed version. He believed in writing everything in one go: „[…] If we cannot, in the flash of a single moment, see a composition in its absolute entirety, with every pertinent detail in its proper place, we are not genuine creators. “ 10, he was not a composer “searching“ for a piece for hours, sitting at the piano. He also was always aware of an instrument’s weaknesses and strengths. Some of the disadvantages of the harp he lists in his book “A Composer’s World” are: the sometimes missing fluency and the uneven sound- due to the sound generation with fingers. The direct contact of player and instrument and the harp’s suitability for chords are some of the advantages he mentioned. The “Sonate für Harfe“ consists of many chords and has no typical virtuoso-writing because quick passages in this piece are only used to create sound fields rather than being virtuoso. To Hindemith, it was essential to understand an instrument to be able to compose for it.11 He was able to play many instruments (the harp was one of the instruments he could not play), something he also asked of his students. Hindemith started his career as first violinist in the Frankfurt opera house, only to become one of the leading viola virtuosos of that time.

Translation

As German markings in scores are not very common and I have seen many mistakes made in the translations; I decided to provide a translation of all the German markings in the score.

Mäßig schnell (3/1/1)12 – moderately fast

Ruhig, ein wenig frei (5/2/1) – Calm, rather free13

Verklingen (5/2/5) – fading/ dying out (perdendosi)

Neu beginnen (5/3/2) – beginning anew (this does not necessarily mean tempo primo!)

Vorangehen (5/4/1) – accelerando

Zurückhalten und verklingen (5/5/2) – morendo

Im Hauptzeitmaß (6/1/1) – tempo primo

Breit (7/1/1) – broad

Im Hauptzeitmaß (7/4/2) – tempo primo

Ruhiger (8/1/1) – calmer

Langsam (8/4/1) – slow

Lebhaft (9/1/1) – lively

Hervor! (10/4/7) – bring out

Sehr langsam (14/1/1) – very slow

Harmonics & dynamics

Elena Zaniboni already wrote about the matter of harmonics in the Sonata but I have to mention this point again, because I want to weaken the theories that lead to the unnecessary discussion lasting for decades.

As Elena Zaniboni states of course correctly –having performed the piece for Hindemith himself- the harmonics should be played on the indicated string. It seems strange, that although there cannot be any doubts about the way the harmonics should be played in that piece, there are still many theories and arguments circulating the harp world.

There are basically three arguments for playing the harmonics one octave lower:

Carlos Salzedo used this notation in his “Modern Study of the Harp” (1921) and being a contemporary of Hindemith, some people state that Hindemith must have used Salzedo’s notation. Hindemith never owned, and probably never even saw an edition of this publication. Another argument for playing the harmonics one octave lower is the following line of the poem “The strings unbidden murmur like humming bees”. In the German version it says “leise wie Bienenton”, which does not refer to buzzing at all –it says the sound of bees. Anyway, the sound of bees might be heard as high or low and should not be an argument for a performance issue. Others say, that because Hindemith notated harmonics in his works for viola that way, harpists should play them like that as well. Hindemith would strongly oppose that, because the Sonata is a work for harp. Everyone acquainted with Hindemith’s oevre and character knows, that it was essential for him to study an instrument carefully before composing for it and thus he would not use the notation of the viola to write for harp. (see previous passage) Apart from the most vital fact – Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi playing the harmonics on the indicated string – there is another argument: When considering the use of harmonics in Hindemith’s other works (e.g. “Drei Gesänge für Sopran und großes Orchester op. 9”, 1917 or “Konzertmusik für Klavier, Blechbläser und Harfen op. 49”, 1930), it becomes clear that orchestration does not allow the other possibility of them being performed one octave lower.

Alas, the main cause for discussions about the Sonata is the dynamic in the last line of the second movement. There is written proof by Hindemith himself that it must be pp.

Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi taught her students to play the last line fortissimo. In the 2004 edition the dynamic notated in the last line of the second movement, is forte, which cannot be justified. In Hindemith’s Erstschrift, the first autograph of the sonata, on the same spot, one can find a fortissimo, see example 1, but in the second autograph, Reinschrift, a pianissimo is notated, see example 2. And in Hindemith’s oevre, the last version is always the one that is valid. That means, that instead of forte, it should be pianissimo (as printed in the first edition from 1940), a mistake that has been corrected in the reprinted edition as of now.

But how was it possible that this mistake ever occurred?

The sonata was printed in February 1940 by Schott, that being the time, when Hindemith was moving to the U.S.A and thus, the sonata was never corrected by Hindemith (which he did with many of his works in the 1950ies). A correction note Hindemith wrote (probably) in 1943 for AMP, does not mention the dynamics of this part. In 1962, having heard the competitors in Israel performing the sonata, Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi wrote a letter14 to Hindemith about the dynamics „Pendant notre correspondence (dans le 1940) au sujet de la Sonate, Hindemith m’avait envoyer les épreuve d’imprimerie et les 6 dernières mesures du II mouvement etaients ff. Aussitôt publiée il n’y a rien écrit, ni ff ni pp. et puisque avant ces 6 mesures il est signé p les interprètes jouent p.- […] et moi, j’a toujours joué ff […] J’aimerai savoir ce que Hindemith aime, peût être avant la pubblication il a changé?“15

As a reply, Hindemith wrote a note on her letter: „Ich weiß nicht mehr, wie das Original war, glaube aber, daß ich für die endgültige Drucklegung, die jetzt geläufige Form (also pp bleiben) gewählt hatte. Sie möge also bitte auf ihr Privat-ff verzichten.”16

In 1989 a German harpist called the editors of Schott and demanded that the next edition was to be changed from pianissimo to forte, because Hindemith himself had told her to play forte17. Then, because of a double-mistake, the “Hindemith-Institut”, confirmed the forte, based on the first autograph (although in this autograph, Hindemith notated fortissimo). The problem was, that until then, it was not clear that the autograph in possession of Schott, is the second autograph and so the dynamics in the 2004 edition were changed.18 Whatever his intentions were, Hindemith was flexible with his work and maybe, when asked, in that exact moment, he preferred forte. But I think, if you want to be one the safe side, there is written evidence for playing pianissimo and, as Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi wrote „Je vous en priè, ecrivez moi le plus tôt possible, car je veux jouer exactement ce qu’il aime car la Sonate a eté dedié á moi et il serait tres curieux de ma part de la jouer… mal.“19

Excerpts of the autographs are being published by courtesy of the “Fondation Hindemith”, Blonay (CH). Unpublished sources (letters, autographs, catalogue), if not stated differently, are being kept at the „Hindemith Institut“ Frankfurt.

Next article: Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi and Paul Hindemith – reconstruction of a cooperation

Lecture-recital “Die Harfenistin Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi und ihre Zusammenarbeit mit Paul Hindemith” (12.5.2016, University for Music and Performing Arts Vienna)

1 As one of the leading viola virtuosos he had a very busy touring schedule until then.

2 Pöschl-Edrich p.22; This has been reported by Carl Swanson. He said, that maybe his teacher Pierre

Jamet told him this story.

3 Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty (1748-1776)

4 See also next article: Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi and Paul Hindemith – reconstruction of a cooperation

5 Pöschl-Edrich, Barbara: Modern and tonal: An analytical study of Paul Hindemith’s Sonata for Harp;

Dissertation – Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts.

Boston University College of Fine Arts, 2005: p. 58

6 Plank, Elisabeth: Die Harfenistin Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi und ihre Zusammenarbeit mit Paul Hindemith und Alfredo Casella. – Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra Artium. Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien, 2015: p. 39

7 Alcaic stanza: (u — u — u | — u u — u —) (u — u — u — u—u) (— u u — u u — uu — ) Bruhn p.44

8 Pöschl-Edrich p.52ff. For a detailed analysis see: Pöschl-Edrich, Barbara: Modern and tonal: An analytical study of Paul Hindemith’s Sonata for Harp; Dissertation – Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Boston University College of Fine Arts, 2005

9 Bruhn, Siglind: Hindemiths große Instrumentalwerke. Waldkirch: Edition Gorz, 2012: p.43

10 Hindemith A Composer’s World, p.84 f

11 Hindemith was able to play many instruments (the harp was one of the instruments he could not play),

something he also asked of his students. He started his career as first violinist in the Frankfurt opera house,

only to become one of the leading viola virtuosos of that time.

12 (page/line/bar)

13 In Grandjany’s copy, “ruhig” has been translated as quiet. But “ruhig” can mean quiet or calm. In this context, being a marking for tempo, it means calm.

14 Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi wrote her letters to Paul Hindemith or his wife Gertrud in French. Her French was

mostly literal translations of Italian phrases. For this article, they have been copied exactly without corrections.

15 „After our correspondence (from 1940) regarding the sonata, Hindemith sent me the first prints and the last six bars of the second movement were in ff. After the sonata had been published, nothing was written [there]. Neither ff nor pp. And now, it says p, and because of that, the performers are playing p.- […] And I, I always play ff […] I want to know, what Hindemith prefers, probably he changed it before the work was published.“

Letter from Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi to Gertrud Hindemith, 9.9.1962

16 “I cannot remember the original version, but I think, that for the printed edition I opted for the current version (staying in pp). She should be so kind as to abstain from her personal-ff.”

Note written by Paul Hindemith on the letter from Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi to Gertrud Hindemith, 9.9.1962

17 Elena Zaniboni tells the same story. She once had the chance to ask Hindemith, so she played both versions for him and he told her, playing forte was “bello!”. (Plank, p.33)

18 Plank, p. 32f

19 „I ask you kindly, to answer me as quickly as possible, because I want to play exactly as he wants, because the Sonata has been dedicated to me and it would be peculiar, if I played it … badly.“

Letter from Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi to Gertrud Hindemith, 9.9.1962